| |

| Insurance, shipping & legal news |

| |

|

Chameleon PandiSA is an independent provider of claims handling, P&I correspondent services, recovery, surveys and risk & insurance consultancy with an emphasis on the shipping, logistics and trading industry that is active on the emerging Latin American continent.

We feel its our task as your local correspondent to share the expertise that we encounter on the LatAm market. Besides giving added value to your business we hope you thoroughly enjoy reading it!

Customer service, availability and flexibility in LatAm. Excellence is not a destination, its a continuous journey...

Offices in Chile and Colombia

|

| |

|

| |

| The liberalization of the Colombian marine insurance market |

| |

Whilst other Latin American countries, such as Brazil and Argentina, have chosen for a more protectionistic policy, Colombia clearly has taken the stand of free trade.

Recently Colombia have signed trade agreements with the US, EU, South Korea, and others such as China are pending. The financial chapter of such agreements is one of the most important and are based on the principles of equal treatment of national and foreign providers.

Why liberalization is required? In many cases, the domestic insurance industry not manages to offer coverage to risks that are increasingly complex. Therefore, in most cases, it comes to international experience and more capital to develop a more robust and innovative insurance market to cover such risks.

Notwithstanding that the Colombian insurance market is already quite sophisticated the internationalization of the insurance market will bring international standards, technical expertise, and extra capital for domestic investment, which will improve the standard of the local insurance industry and its know how.

Policy makers also acknowledge that the typically larger commercial risks, such as aviation, maritime and international transport are already covered by global foreign insurance companies through reinsurance, fronting vehicles, reinsurance brokers, etc.. This implicates that when currently placing a risk abroad a local insured should go via a local (re)insurance broker, which on its turn should ask a domestic fronter to issue a local policy on behalf of a Colombian registered reinsurer. Direct insurance will ensure its all less complex, and less intermediaries and commissions involved.

The Financial Reform Bill was passed into Law 1328 of 2009 and facilitates this for all MAT insurance business and will come into force on 15 July 2013. As of that date foreign insurers will be able to provide aviation and marine insurances on direct basis (as opposed to retrocession/ reinsurance). It will be permitted to provide insurance cover for (i) vehicles, (ii) commodities being transported, (iii) general liability arising therefrom as well as (iv) insurance cover for international transit.

Additionally foreign claims handlers and consultants can offer these auxiliary services in Colombian territory. Also foreign insurance intermediaries can offer these insurances in Colombia.

Colombia has recently overtaken Argentina as Latin America's third economy, being almost the size of Spain and France together, combined with a high potential in insurance penetration, double digit increases in marine insurance premiums and loss ratios of 30% Colombia is highly interesting for foreign insurers that want to explore less saturated markets.

For any further information, assistance, registration and other legal advisory please contact Claudio Bruyninx: response@pandisa.com

|

| |

|

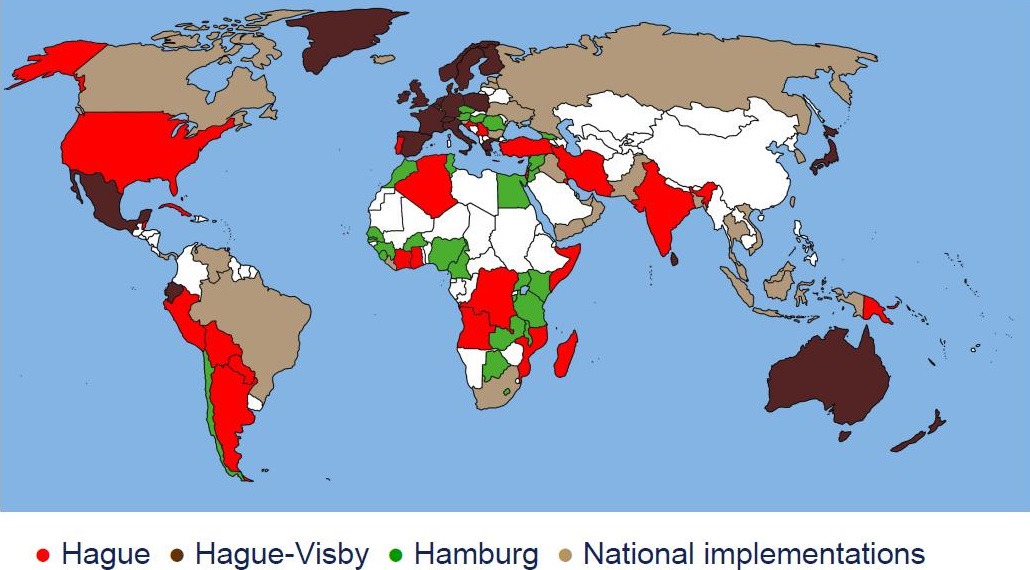

| Ocean transport conventions per country |

| |

|

| |

The above picture shows the ocean transport conventions applicable per country. You will deduct that there are some white spots that are not covered. In particular we would like to shed some (high)lights on the law applicable in Colombia (white spot left above).

The “civil” responsibility of the so called maritime operator is laid down in the Colombian Code of Commerce.

The ambit of the application starts when the carrier has received the good until delivered to the consignee. The presumption of guilt falls on the shoulders of the carrier, if he would like to call upon one of the exoneration grounds he will have the proof the causal connection between the damage and fault.

In respect of limits of responsibility if the shipper declares the value of the cargo on the transport document the carrier is maximum responsible for this amount including freight costs. If not declared the shipper bears the responsibility to proof the value of the cargo.

In accordance with Article 1609 of the Code of Commerce, the carrier shall be relieved of liability for loss or damage arising from:

1) Nautical fault of the captain, the pilot or the staff assigned by the carrier for navigation.

2) Fire, unless the responsibility of the carrier is proven;

3) Perils of the sea or other navigable waters;

4) Force majeure, such as acts of war or public enemies, arrest or seizure by governments or authorities, riots or civil disturbances, saving or attempting to save life or property at sea

5) Quarantine restriction, strikes, lockouts, stoppage or restraint imposed wholly or partly to work, for any reason whatsoever;

6) Inherent vice

7) Insufficient packaging or marks

Furthermore a time of two years is applicable as of the moment that the contract of carriage ended.

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/2012/11/22/3108959/as-panama-canal-expands-latin.html#storylink=cpy

|

| |

| Supreme Court rules on extent of inherent vice exclusion |

| |

|

| |

Global Process Systems Inc & another v Syarikat Takaful Malaysia Berhad (The “Cendor MOPU”) Supreme Court [2011] UKSC 5

This significant decision of the Supreme Court has examined and clarified the extent of the exclusion of losses by inherent vice available to insurers under the standard Institute Cargo Clauses that are regularly incorporated into marine cargo policies.

The case concerned an oil rig, Cendor MOPU, that was being transported from Texas to Malaysia on a barge. The rig had three large tubular legs in place extending some 300 feet into the air. During the voyage the barge called at Saldanha Bay near Cape Town where some repairs were made to the legs. The voyage resumed and, while off South Africa, one of the legs broke off and fell into the sea. The other two legs fell off the rig the following day.

The oil rig was insured under a marine cargo policy that incorporated the Institute Cargo Clauses (A) (1982). Various perils are excluded from cover under the Clauses including, by Clause 4.4:

Loss, damage, or expense caused by inherent vice or nature of the subject matter insured.

The owners of the rig claimed under the policy for loss caused by perils of the sea. The insurers denied the claim on the basis that the loss arose from the weakened condition of the legs, which they said comprised inherent vice. The insurers’ position was accepted at first instance but then rejected by the Court of Appeal.

Before the Supreme Court, the insurers relied on the definition of inherent vice by Lord Diplock in Soya v White [1983] that inherent vice was the risk of deterioration of the cargo because of its natural behaviour in the ordinary course of the contemplated voyage but without the intervention of any fortuitous external event. The insurers argued that the type of waves the barge and rig encountered off South Africa were quite foreseeable and usual for that area and time of year and were accordingly not an external event.

The Supreme Court rejected the insurers’ argument. The Court held that Lord Diplock’s reference to “the ordinary course of the contemplated voyage” was not intended to encompass weather conditions that were foreseeable on the voyage, but was in contradistinction to a voyage on which some fortuitous external accident or casualty occurred. Anything that would count as a fortuitous external accident or casualty would suffice to prevent the loss being attributable to inherent vice.

The Court came to the view that the loss of the rig’s legs had been caused by a fortuitous external accident or casualty of the seas. This followed from the rolling and pitching of the barge in the sea conditions encountered whereby a strong “leg-breaking wave” struck the rig at such a moment as to cause one of the legs to fall off. This then lead to increased stresses on the remaining legs and their subsequent breakage the following day. The loss was not caused by inherent vice of the legs.

The Supreme Court’s ruling is likely to have the effect of severely curtailing the availability of the exclusion of inherent vice to insurers under the usual marine cargo policies that include the standard Institute Cargo Clauses. The exclusion is now only likely to be available where the loss arises solely from the nature of the cargo itself and irrespective of any external events or factors.

|

| |

| What constitutes a fixture? |

| |

|

| |

When parties agree the main terms of a C/P such as the freight, voyage/time, cargo, destinations a so called "fixture" has been agreed. Whilst the details to be agreed afterwards.

Jurisdictions have different views as to which point a fixture is binding. Canadian and US jurisprudence will agree that a binding contract has been agreed when the main terms are concluded.

However, most C/P are governed by English law, which adopts a different view. English contract law argues that all terms (specific and general terms) have to be concluded before an agreement is valid. Hence either party can step out the agreement without any damages to be paid to the counter party.

In any event the recap should provide the words 'subject to details' in order to avoid a binding fixture. Other derivatives or alterations such as for example 'subject to logical amendments' are to be avoided in all cases.

Furthermore in order to prevent later discusions and eventually a legal debate we would advise that both the owner and charterer agree a date untill which the fixture is kept open. In that way the owner cannot walk away before the deadline has reached. If he would do so, under the principles of offer and acceptance under English contractual law the charterer would be entitled to damages for the loss of the fixture.

Any further remarks or questions please send a message to: response@pandisa.com

Source: Professor Richard Williams, Swansea University, Charterparty Contracts, 4-9

|

| | | |